The Mother's Web

The audiobook of Charlotte’s Web is an astounding thing to listen to. It really is not a modern story at all, and it has much more in common with the ancient myths, scriptures, and fairy tales. In short, the story is really not about lovable farmyard talking animals. Instead, it is about the ancient pattern of how the feminine saves ‘from above’.

Charlotte’s Web

In Charlotte’s Web, by E.B. White, there is a feminine protagonist (Charlotte the spider) who saves her young friend (Wilbur the pig) from death by convincing the farmer (Mr. Zuckerman) to spare his life through the use of a “miraculous” woven object (her web). It should be said that this is a very low-resolution summary of the story and it is by this method that the symbolic pattern is visible.

Although Charlotte is not the pig’s mother, she takes that role because she is moved by witnessing his loneliness one night from her vantage point of her web hanging over the pig pen. She subsequently decides to find a way to save Wilbur’s life. The method she uses to accomplish this is by weaving written words into her web in the doorway above the pig: “some pig”, “terrific”, “radiant” and “humble”.

Of course, when the farmer sees the words, he is astounded and calls it a “miracle” In the end, he becomes convinced that this pig is a special one. Rather than butchering him as he would a typical spring-pig, he keeps Wilbur in the barn - fat and happy to the end of his days.

In one sentence, you could say that the story is about how a spider saved a pig by weaving a web. It is important here to notice that the spider does not save Wilbur by violence. (She could have perhaps killed the farmer with her venomous bite.) Instead she saves Wilbur- as if he were her beloved child- by covering him from above with a miraculous, or even magical, woven garment.

The feminine saves by covering

Once you see this pattern of saving-by-covering, you will start to notice it in many other stories, including fairy tales, myths, narratives of the saints, and especially the stories of the Bible.

Take for example the story of how Rebekah intervened to grant the birthright to Jacob by clothing him in goat skins, or the story of how Rahab saved Joshua by hiding him on her roof under a bundle of flax. But the ultimate version of this is found in the story of the Incarnation, where the Blessed Mother clothes Christ in flesh. It is significant that traditionally she is depicted as in the process of sewing the veil of the Temple during the event of the Annunciation.

Depiction of Mary sewing the temple veil when the Angel Gabriel announces the incarnation of Christ, featured on the holy doors of a church in Sarajevo (credit: Wikipedia).

Guadalupan covering

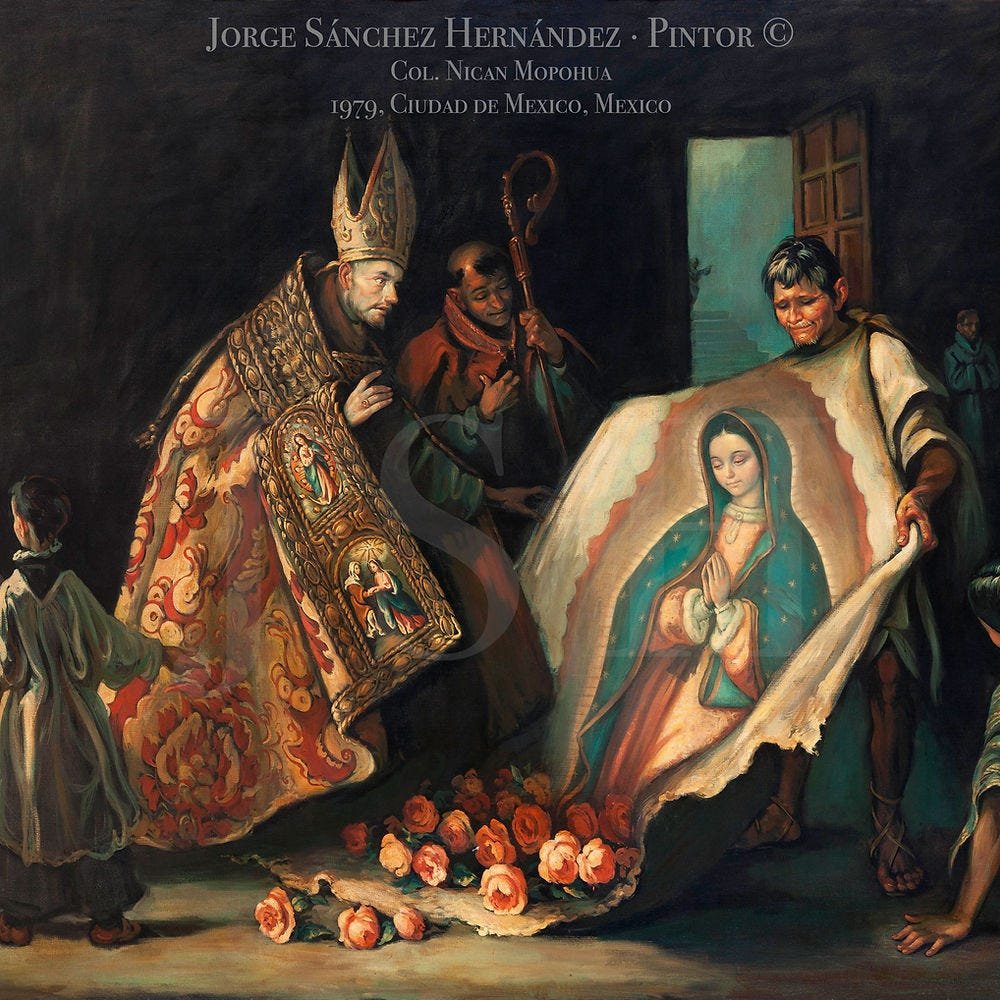

Turning to the story of Our Lady of Guadalupe, you may be just as surprised as I was when I realized that it shares the same symbolic structure as Charlotte’s Web. In that story, the Blessed Mother intervenes to save her children (the peoples of the Americas) by clothing them with something miraculous. In Charlotte’s Web, this miracle is a spider’s web with words on it, but at Tepeyac, the miracle is a tilma with an image on it. In both cases, the mother clothes her children with a special woven garment ‘from above’.

But this pattern is visible in our daily lives as well. Isn’t it true that a mother has a special role to play in clothing her children? She ‘knits’ her children in her womb, weaving ‘garments of skin’ for them. Grandmothers and mothers often sew baby blankets and clothes to cover the newborn babies. As children grow, it is often the mother who desires to pick out clothes and even make them herself. This pattern touches on something fundamental to the maternal spirit.

(credit: Jorge Sánchez Hernández, ca 1980. Juan Diego desplegando el manto. oil on canvas.)

With this in mind, I return to the story of the Blessed Mother’s apparitions at Tepeyac with newfound love. She came to us then (and still today) to do for us what she did for Christ: she clothes us with herself. You only need to take a look at the popular way her devotees wear her image today. You can find the Virgin of Guadalupe on t-shirts, flags, carhoods, murals, hats, and virtually everything. It is undoubtably one of the most readily recognizable images of devotion - even in this secularized world - today.

But it is not an accident that her devotees wear the image on anything they can screenprint. It is an integral part of the story itself.

She covered Christ with flesh so that His flesh is her flesh. His most Sacred Heart comes from her Immaculate Heart. She covered Him to cover us all. And by covering us all, she presents us to the Father (mystically through Christ) as under her veil, wrapped in the garment she has woven for the Son. In this way, when the Father sees us, He sees His Son, and when He sees the Son, He sees His beloved one from the beginning.

It is significant in the story of Guadalupe that Juan Diego brings her flowers. The text of the Nican Mopohua says that she ‘arranges’ the flowers in the tilma and then commands him to bring them only to the Bishop. This ‘arranging the flowers’ is the moment when the Blessed Mother imparts her image into the fabric of the tilma. The flowers serve as the ‘raw material’ out of which she weaves her miracle.

That moment was like a little incarnation since after all, Our Lady appeared as a pregnant mother on Tepeyac. Indeed you can see the pattern of birth here as well because Juanito (bearing the image of his mother) is presented to his father (the Bishop), and the Bishop comes to recognize that his mother has sent her son (Juanito). You could say that the Bishop here recognizes Juanito as the legitimate son and heir because of Mary’s covering over him

To be like Juan Diego is to be covered in the image of our Blessed Mother. After the temple was built to house the tilma, Juan Diego became a hermit, living on the grounds of the shrine. He became a father to pilgrims and a herald of Christ, spending the rest of his days there, living under the miraculous image.

Duccio di Buoninsegna, Madonna of the Franciscans, c. 1300, Tempera on wood, Pinacoteca Nazionale, Siena. (https://www.italianartsociety.org/2016/09/the-virgin-of-mercy-madonna-della-misericordia-is-a-marian-devotional-image-type-recognizable-by-its-portrayal-of-mary-protecting-those-in-need-and-devotees-under-her-blue-mantle-cloak/)

The veil, the wall, and the church

The veil - the covering- is an important part of the iconography and symbolism of the Mother of God and the feminine in general, and now with the pattern of ‘saving-by-covering’, I think the coherence of this pattern is more understandable.

Both in the story of Charlotte’s web and the Guadalupan narrative, the mother weaves a miraculous garment and covers her children in distress. By doing this, she claims the children as her own. She protects them. She hides them under and inside herself.

There are many variations of this pattern in art and iconography of East and West, including the above image which represents the madonna della misericordia form. There are also two remarkable Eastern types which connects the concept of the veil, the wall, and the church.

Under her wings Icon, Russian (credit: The Icon Museum, Kampen: Ikonemuseumkampen.nl)

The first type shows the Mother of God protecting a group of people under her veil and connects this to psalm 90 which describes seeking refuge “under your wings”. So this icon connects the image of the protecting veil with the wings of a mother bird, as well as the walls of the city shown behind the figures.

These three images go together here as symbols of the boundary between inside and outside. The veil and the wings are related to interiority, softness, closeness to the heart. The walls of the city represent the same concept on the scale of the city.

In the scriptures and throughout the Christian tradition, the city is seen as a mother who guards her children within her walls. Take for example the tradition surrounding the protection of the Mother of God over the city of Constantinople. In the below icon, the veil of Mary is depicted as a white garment which she suspends over the city, under which the people are protected. But this image goes even further than the other images.

The icon of the Protection of the Theotokos connects the images of the protecting veil of Mary, the walls of the city, and the temple. It specifically depicts the event of the apparition of the Blessed Mother in a church of Constantinople, which was seen by St. Andrew the Fool for Christ. In this scene, the Mother of God is shown as the figure that protects the people by housing them under her veil, within her walls, and inside the Church. In this symbolism, these are the same thing. Indeed, the Mother of God herself is the veil that hides and covers the divine child who is present but not seen in this image.

The Protection of the Mother of God (Credit: https://www.oca.org/saints/lives/2000/10/01/102824-the-protection-of-our-most-holy-lady-the-mother-of-god-and-ever)

Hide us under your veil

The veil is part of the super power of the feminine. It miraculously hides and protects loved ones under herself. It is a sacred boundary like the wall of a city. The feminine covering claims her children and rejects enemies.

This pattern has so much vitality and it runs so deep in our humanity that it simply cannot be avoided. I hope this post helps people to appreciate a little more the symbolic coherence of this pattern in art and human experience.

Miguel Salazar is a frequent participant in our second-Monday book discussions, where he always contributes insights and humor to a lively conversation. He’s now writing as Hungry Coyote on Substack, where this article first appeared.